|

| Shirt commonly worn on St Patrick's Day. |

Today I watched a green horde of

drunken students staggering their way down main street of Amherst Massachusetts, draped with chintzy plastic beads, or oversized lopsided

caricatures of top-hats, manufactured in factories overseas for

novelty companies. “Kiss me I'm Irish” shirts were stained with

vomit and alcohol, while slurred speech made incoherent by cheap

liquor demanded junk food across counters. And it wasn't even St.

Patrick's day. Today has been branded “Blarney Day” in the town

of Amherst, a preemptive St. Patrick's day of sorts. Created by the

local bars, several of whom boast “Irish Pride” it targets the

large student market which ships off to repeat the same delinquent

behavior over spring-break, when St. Patrick's day really occurs. The

atmosphere is a cheap drunken haze in which a semblance of Irish-ness

is about as genuine as the discarded plastic shamrocks, stamped with

Budweiser's seal of approval, which litter the street. Across the USA, to millions of

bar-goers, this is what it means to be Irish. Students will later

totter home or fall asleep on couches and floors, blissfully unaware

that just a century beforehand, approximately 400,000 starving

immigrants, from whom many are descended, struggled for their lives

and cultural identity in the social battlefield between the

Protestant hegemony, and the Catholic minority.

So many are familiar with the image of

the leprechaun. Around this time in grammar schools across the

nation, children are cutting out little shamrocks and learning that

an ancient saint drove the snakes out of a far away land called

Ireland. Somehow the jolly little redheaded defenders of rainbow

hoards are related, but who really knows how, or why. Within a decade or so, many of these children will join the slow moving masses as they

trudge in and out of bars looking for the next cheap drink, clad in

green. It might as well be Robin Hood or Peter Pan day, but it isn't.

The word “Irish” is found across an assortment of trinkets, (right next to

a brand name of course) all geared towards the sale of that great

motivator; booze, and what a motivator it is. According to a survey

done by Yahoo.com, St Patty's day is the fourth most popular drinking

day in the US, right behind the Fourth of July- even outranking

Thanksgiving. Disregarding the prestige of Yahoo.com, it would seem nonetheless that Irish-ness is as American as apple pie; simply part of the heritage- a shameful misrepresentation of the

painful history of the Irish in America.

The history of the Irish in America

begins with an everyday item; the potato. Eryn's Isle, or Ireland as it

is more commonly known, is a harsh land. Principally suited for

grazing livestock, the labor associated with this industry was

toilsome. As a result, a cheap food source rich

with nutrients was necessary to support the population. The potato was brought to Ireland by

the Basque fishermen who sailed there on their way home from fishing the Grand Banks off the coast of Massachusetts during the 16th century. The potato

eventually became the staple of the common diet, and the cottier

system was established, to ensure the steady production of this

commodity. The cottiers were a class of sharecroppers-mostly

Catholic, to whom Protestant landlords leased poorly maintained land

(at a considerable sum) for the production of potatoes and other

agricultural commodities. Ireland became increasingly dependent upon

this class for survival, and the cottiers suffered. In the early 18th

century, Ireland was still in recovery from the Famine of 1740,

caused by a period of intemperate weather felt across the breadth of

Europe. In 1840, disaster struck again. An Oomycete bacteria infected

the potato crop, crippling the food supply, and bringing Ireland to

its knees in an unprecedented famine. The death toll is uncertain due

to poor resources, but it was estimated that nearly 40% of Ireland's

population perished during the famine. This, combined with Protestant

aggression and growing civilian violence forced many Catholics to

leave their homeland, and go across the sea to the United States,

which beckoned with the promise of food, and freedom from the abuses

of the cottier system and the protestant government. What awaited was

hardly better.

The Irish had traveled in droves to the

United States before, during the previous famine. These were quickly

pressed into indentured servitude, an estimate being that 9 out of 10

indentured servants were Irish, 75% of whom were catholic. Catholic-Protestant tensions had made their way to North America long before the

Irish had flocked to their shores to escape the first famine. Francis Drake led raids against the Spanish colonies of Georgia and Florida, burning and pillaging in the name of

the Protestant Queen. An Irish Catholic was no better than a Spanish

Catholic in their eyes. The attitude had changed little by the time

the immigrants of the potato famine made their way to America. Signs

were posted in business windows, saying NINA, or No Irish Need Apply. Businesses would not open their doors, and many of the Irish of the northern states were quickly pressed into horrific work and domestic

conditions in the dreaded mills of the industrial age, which belched

a thick layer of pollution over towns such as Lowell Massachusetts. Tenements,

small cramped apartment buildings run by slumlords were packed with 10 families to a

room- many of which were only the size of a prison cell. There was no privacy, and there was no food. Starvation and

disease ran rampant through these buildings with large families

packed together in close proximity like sardines in a can, festering in their own filth and unable to move.

The mills kept the Irish dependent upon them by “providing” housing at a steep cost which ensured a compliant and stationary

workforce.

In this time of turmoil and depression, one of the few tokens which remained of the homeland was St. Patrick's day. The immigrants were lost within a culture that institutionalized the anti-Catholic sentiment of Britain and systematically attempted to destroy the Gaelic language by punishing children for speaking it in schools- a systematic attack upon Irish culture. There were few pleasures left to be had. The tradition of imbibing alcohol on St. Patrick's day was linked to a legend in which St. Patrick was given less whiskey than he had ordered. He told the innkeeper that he would be plagued by a demon which fed off of dishonesty, and thenceforth he was served the proper amount. The tradition served to honor the right of the working man by giving him his "measure of whiskey-" in essence, the right to life's simple joys, something which the immigrants were routinely denied within the strictly Protestant confines of America. Alcohol served to alleviate depression, and was integral to the day which celebrated memories of the land they had left behind. Many had come to American shores with the intention of eventually returning home wealthy men. many sent money home routinely, along with correspondences. Husbands left wives and children behind to fend for themselves, promising to return and sending them money- as little as they could. As a result, love and longing for the motherland fills the drinking songs of Irish-Americans rather than resentment towards a country which in reality wanted them as much as America. They were a people whose home existed only as an idea. Resentment was instead reserved for the United States, famously exhibited in the bitter anti-war ballad, Paddy's Lament. War was to destroy the hopes of thousands of Irish, and shatter the dream that they might return to a better life in Ireland.

In this time of turmoil and depression, one of the few tokens which remained of the homeland was St. Patrick's day. The immigrants were lost within a culture that institutionalized the anti-Catholic sentiment of Britain and systematically attempted to destroy the Gaelic language by punishing children for speaking it in schools- a systematic attack upon Irish culture. There were few pleasures left to be had. The tradition of imbibing alcohol on St. Patrick's day was linked to a legend in which St. Patrick was given less whiskey than he had ordered. He told the innkeeper that he would be plagued by a demon which fed off of dishonesty, and thenceforth he was served the proper amount. The tradition served to honor the right of the working man by giving him his "measure of whiskey-" in essence, the right to life's simple joys, something which the immigrants were routinely denied within the strictly Protestant confines of America. Alcohol served to alleviate depression, and was integral to the day which celebrated memories of the land they had left behind. Many had come to American shores with the intention of eventually returning home wealthy men. many sent money home routinely, along with correspondences. Husbands left wives and children behind to fend for themselves, promising to return and sending them money- as little as they could. As a result, love and longing for the motherland fills the drinking songs of Irish-Americans rather than resentment towards a country which in reality wanted them as much as America. They were a people whose home existed only as an idea. Resentment was instead reserved for the United States, famously exhibited in the bitter anti-war ballad, Paddy's Lament. War was to destroy the hopes of thousands of Irish, and shatter the dream that they might return to a better life in Ireland.

|

| Conditions of an Irish Tenement. These would be filled with families. |

During the first few waves of 19th century Irish

immigration, Civil War was brewing in the United States between the North

and the South. As thousands of Irish immigrants spilled by the

boatload into the cities of New York and Boston, the Union began to

recruit. Men who spoke only the homeland language of Gaelic were

given papers which they believed to be documents of citizenry.

Eagerly signing, they were confused when they were directed away from

their families to tables laden with military gear. They had been

tricked into signing enlistment papers. If they wanted to be

Americans, they'd have to be willing to die first. Entire regiments,

famously that under General Meagher served in the War, and along with

German and Italian immigrants served as the expendable shock troops

on the front lines. Proper equipment was reserved for the Protestant

Anglo “natives.” Without adequate ammunition the Catholic

immigrants were hacked to pieces and bayoneted to death before they

had even seen a home. They were simply replaced by the next boatload.

Pensions were rarely given, and their families, without the money

required, often starved to death. Wives went to the mills and

resorted to prostitution to support themselves in their husband's

absence, and the children quickly followed.

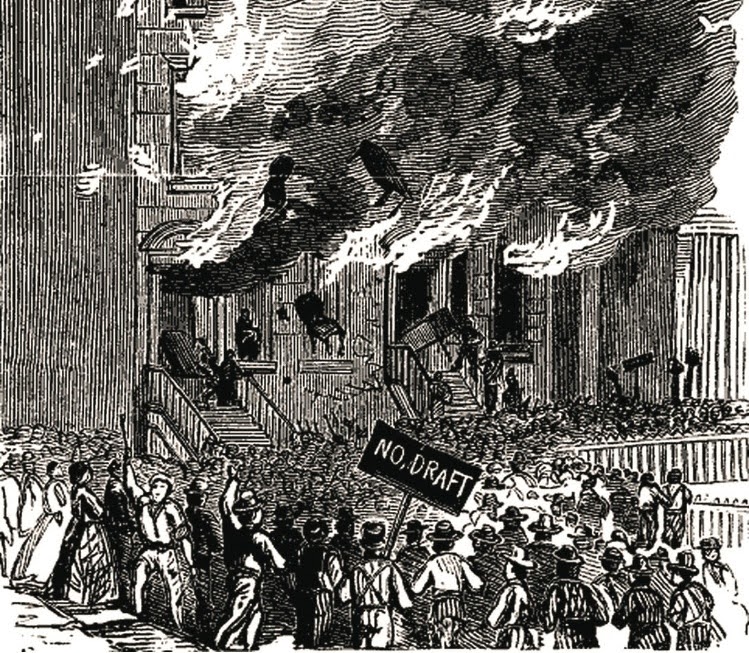

As more and more Irish died and wealthy naturalized citizens dodged the draft for $200, a

|

| Artists depiction of the 1863 Draft Riots of New York |

St Patricks day became a rare moment of nationalism for the Irish. They continued to celebrate their heritage, as the memory of their homeland and the families they had left faded with time, and was all but forgotten with the passing of generations. In their harsh homeland, the symbolism of Whiskey, a pint of Guiness or a Beamish stout was one of small pleasures in a

life of toil. In the hardship of the United States, pubs served as gathering places for these insular communities, a relic of the motherland. As depression, starvation and delinquency continued to

pervade the Irish-American communities, The WASP hegemony seized the

opportunity to portray the Irish as drunkards and louts to maintain

the status quo and keep the Irish where they wanted them- subjugated in

their mills and unable to climb the social ladder.

Violence and discrimination

toward the Irish exists worldwide today. It was only in 1972 that

British forces opened fire upon Irish civil rights protestors,

killing 26 and wounding more in the even immortalized in the U2 song, Bloody Sunday. Today, Irish soldiers have been reportedly

treated with extreme prejudice within the British military. In Perth Australia, a bricklayer posted a NINA sign in 2012 which declared that he would not hire any Irishman on that grounds that

they “too often fake ID's”; a parallel to America's own policies

regarding modern immigration. Throughout Australia today, the Irish still face violence,

which can result in death. In 2002, Julie Burchill wrote an

intensely anti-Irish column in the Guardian, comparing them to

“Nazis,” and “child molesters.” In 2013 an Irish

flag was burned publicly in Liverpool, England. More subtly, the fad of mocking red-haired individuals, referred to as "gingers" within the United States is a lingering remnant of the derogatory stereotype of the Irishman whose hair matched his temperament, and served as a convenient and denigrating marker within society. Red-haired citizens were treated with contempt and admonition on these grounds, and the often parodied slogan that "gingers have no souls" triggers a painful memory of a time not so long ago when such words were accompanied by violence.

The maintenance of such a harmful image

is damaging. Irish persecution has been largely swept under the

rug, and the people themselves assimilated into the all-encompassing white identity. However, the blatant disrespect and hypocrisy of Saint Patrick's Day appropriation is

stunning, especially when it is considered that dialogue concerning

the stereotyping of Irish culture is relatively silent. Why in a society which

so vehemently condemns cultural appropriation is this allowed to go

unchecked? In a town as liberal as Amherst, no one stands in the

street protesting. No one raises an eyebrow. An article about the

tradition of Blarney Day even gives hangover tips for the students. Massachusetts Daily Collegian contributor Emily Brightman refers to

the holiday as an “absurd drinking extravaganza.” That this popular image is unquestioningly associated with a day of cultural pride for a demographic upon whose

backs this nation was built is appalling. What is more appalling is

that no one seems to care, or question the status-quo. Could it be that it has simply become too enjoyable? Another moral obligation pushed aside in the mad rush to the nearest bar?

We can continue to criticize Katy Perry, or Redskins fans, but next time we don our leprechaun hats, plastic beads and head out to hit the bars with friends, let us raise a glass to the innumerable Irish-American men and women who bled, suffered and died for that self-same right, and wonder if the Irish costume is in better taste than that of a Geisha.

We can continue to criticize Katy Perry, or Redskins fans, but next time we don our leprechaun hats, plastic beads and head out to hit the bars with friends, let us raise a glass to the innumerable Irish-American men and women who bled, suffered and died for that self-same right, and wonder if the Irish costume is in better taste than that of a Geisha.

No comments:

Post a Comment